The (RE) Series: (Re)constructing How We Talk About The Outdoors

In Part One of the (RE) Series, I shared my grandmother's love for nature which she passed on to me. To us, the outdoors represents love, healing, community, and boundless freedom. Many of us understand this power, but we must also address the tools used to exclude people of color from outdoor spaces. To change the future, we must confront the past and the present.

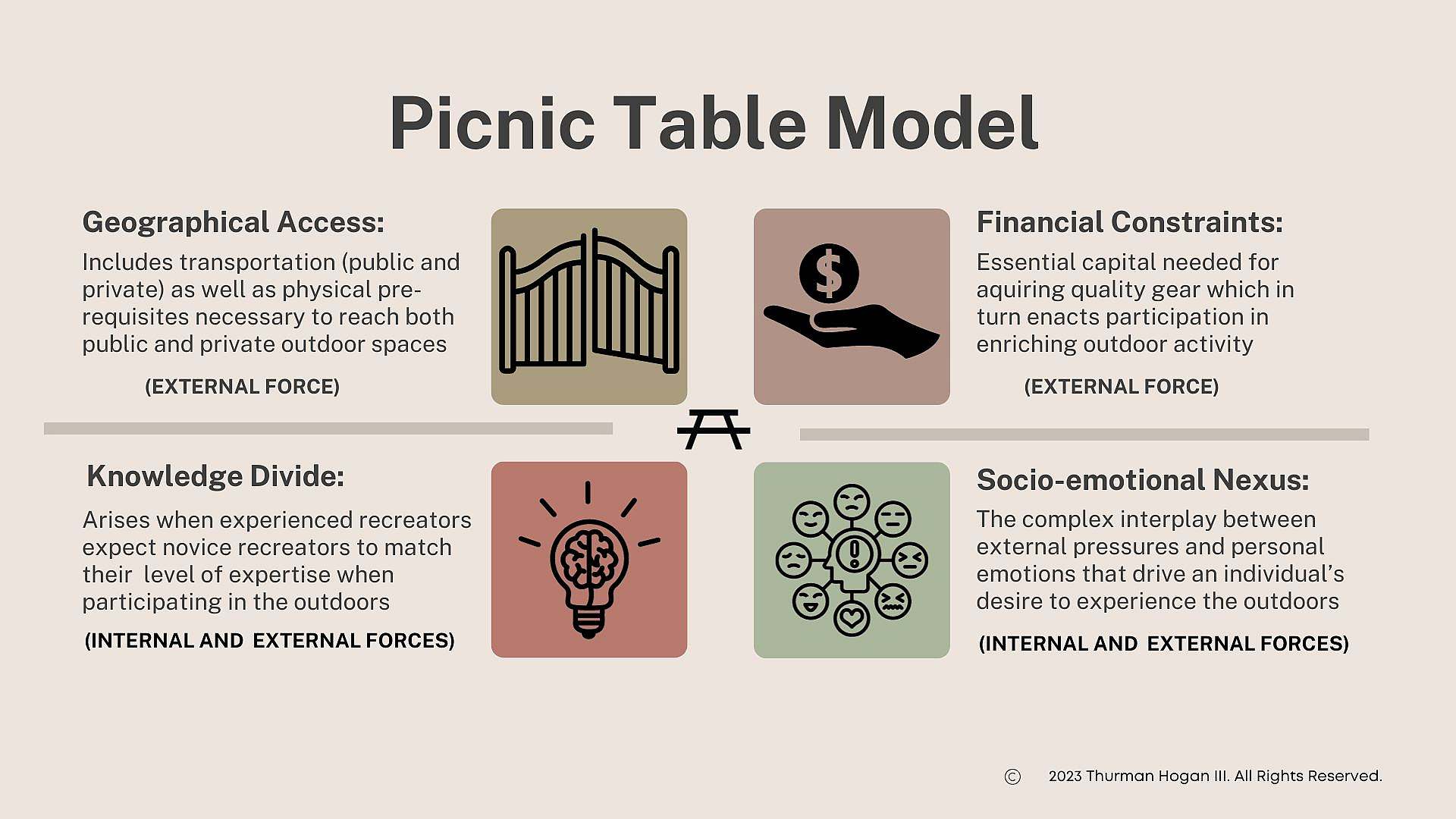

Part Two dives into the four main barriers I’ve observed when in the outdoors. These four main barriers comprise what I call The Picnic Table Model (below). This model will frame our conversation about barriers youth and people of color face when trying to participate in outdoor activities.

Access to the outdoors ought to be a universal right, but this wasn’t and isn’t the case currently. For Black people, outdoor spaces have historically been places of disenfranchisement. This disenfranchisement was systematic, intentional, and enforced through practices like Jim Crow, segregation, and white supremacy. Decades of these egregious practices fostered a cultural norm in our society where Black voices were not heard and Black bodies were not protected.

This isn't meant to be a history lesson on Black oppression but the past helps us understand the present. Other resources exist to better explore the history of Black oppression in America. Consider the book Contested Waters by Jeff Wiltse which looks at the history of segregation of municipal pools in the United States. These intentional and systematic practices did not end at the change of the century–they are alive and well today.

The Picnic Table Model was created based on my personal outdoor experiences and the experiences of other outdoor leaders from the Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) community also played a part in the creation of this model. Observations while working outdoors with youth of color also helped shape this model. It allows us to observe the four main barriers youth (and people of color) face when accessing the outdoors.

While not the sole way, The Picnic Table Model serves as a starting point for an honest conversation in how we look and talk about the disparities for communities of color in the outdoors.

I named it The Picnic Table Model because picnic tables play a vital part in the outdoor experience but often get overlooked. They serve as a place of fellowship, rest and refuge, and lasting memories. A barrier-free outdoor experience allows picnic tables to be the beacon they are. In the same light, a barrier-free outdoor experience allows for youth and people of color to embody their true selves.

Geographical Access:

In my home state of Texas, over 95% of the land is privately owned according to the Texas Land Conservancy, leaving less than 5% accessible to the public. Texas State Parks offer a range of activities, but they're often located 10-plus miles from city centers, with no public transportation options. This raises questions: how are people without private transportation supposed to access these outdoor spaces?

Booking trips for groups can also be challenging when parks lack group sites. This often leaves organizers at the mercy of private landowners (summer camps, retreat centers, etc.), which creates scheduling conflicts and further hinders accessibility. Some facilities can be so underutilized that it becomes discouraging for organizations that don’t have land of their own.

At the organization I work at, Black Outside Inc., we have toured many private facilities in Texas to partner with. When we ask what their biggest area of weakness is, there is a common theme of not knowing how to reach people (especially those of color) to come out. Because of this, their property just sits and doesn’t get used or is poorly utilized. This in turn ultimately leave(s) outdoor spaces underutilized by people of color and the land owners.

Financial Constraints:

Before I unpack this barrier, I need to say that you can recreate with whatever gear you have and can afford. Do not let equipment hold you back from experiencing the outdoors. Contrary to belief, you do not need expensive gear to enjoy basic activities outdoors. It's perfectly fine to pull out that cooler that's collecting dust outside, pack it with sandwiches and drinks, and go have fun at a park.

However, if you want to kick it up a level in the type of outdoor activities you want to do, gear can be cost-prohibitive. Walking into an outdoor store, you can expect to spend anywhere from $100-$200 just on a single 30L daypack alone. For some, the initial investment cost can be high and deter people from being outdoors.

Fees such as entrance and activity can further compound financial constraints, especially for low-income families who already face transportation expenses. If that same family wants to do a water sport such as kayaking, they can expect to incur another additional cost. We know park and activity fees go towards good work–I am in no way advocating against them, but let’s be real; choosing between paying park and or activity fees for the family or buying groceries becomes a harsh reality for some.

The biggest barrier in the financial constraint category is the opportunity cost. In Black and Brown communities, the principle of ‘time equals money’ rings true and hits a little harder for families living paycheck to paycheck. Do you sacrifice a half day at a state park to recreate or do you use that time to pick up extra shifts? Some might argue that the physical and physiological benefits deem outdoor experiences invaluable for families, but that’s not stopping the stack of bills sitting in the mailbox when they get home. Rent will still be due and bills will still have to be paid. In today’s world, you have to have a financial cushion and work flexibility to do #Vanlife, rock name-brand gear, and visit the cute Airbnb you saw your favorite outdoor TikTok influencer stay at for free. These freedoms aren’t always an option for those living paycheck to paycheck and we have to be mindful of this reality.

Knowledge Divide:

One time, I was guiding a backpacking trip and was impacted by the knowledge divide. A few of the staff and I were taking around 15 students to Lost Maples State Park here in Texas. Outfitting a trip for 15 people naturally requires more specialized gear than a solo trip. Also, keep in mind this was the first time we as a staff led and guided a backpacking trip at our organization. Therefore, I had questions about the gear we were bringing. Park staff cleared my gear over the phone and assured me that I shouldn’t have any problems.

During the primitive backpacking trip we faced a disheartening incident. While preparing dinner, neighboring campers, driven by curiosity, reported us to a park ranger, alleging a rule violation. Upon arrival, the ranger escalated the situation, deeming our actions a serious infraction, and threatened to confiscate previously approved gear and issue a citation. Compliance was the only option I had to avoid further consequences. This encounter should have been an opportunity to educate. In reality, it left a lasting mark on our experience, deterring me from returning to that location, despite it being one of the most beautiful parks in my opinion and considered a good place for first-time backpackers.

In outdoor communities, experienced recreators often enforce and impose their expectations on novices. For people who don’t look like the “traditional recreator” that they are used to seeing, there is extra scrutiny placed on us, requiring us to have the burden of proof that we belong in these outdoor spaces. Since information is largely passed down in the outdoor community, how do you teach, mentor, or relay information in a way that won’t discourage people of color from the outdoors? We as an outdoor community need to remember that there is a strong correlation between negative experiences outdoors and the probability that a person will return.

Socio-emotional Nexus:

Reflecting on my experiences at a predominantly white high school, where classmates indulged in winter getaways to Aspen and Vail, spring breaks in Destin and Seaside, and summer trips across Europe, revealed stark disparities in outdoor access.

As one of the few Black students in the entire school, I grappled with intimidation when invited to participate in activities like bass fishing, trap and skeet, and hunting, which my peers often engaged in on private ranches and ponds. Being invited to these excursions was both a compliment and a challenge, triggering a sense of over-preparation. Late-night sessions on YouTube, Reddit, and online forums became my routine to familiarize myself with the activities and their lingo, navigating the pressure to perform and fit into unfamiliar environments.

When surrounded by individuals who shared my background during these outdoor outings, the pressure to perform dissipated. This type of fellowship fostered an authentic connection with nature, highlighting the transformative power of representation. It was during these outings, filled with fellowship, jokes, and shared music experiences, that I truly felt a sense of belonging.

Having representation of diverse people in the outdoors can help curb the external pressures that White space puts on us. This allows us to be able to have community and belonging. When I don’t have the external pressure or feel like I am representing all Black people I get to bring my culture and traditions into these environments. I sing and dance to ‘I Like It’ by DeBarge when my food is rehydrating, bring Lawry’s seasoning on backpacking trips, and bring my Jergen’s lotion so that I am not ashy. A feeling of belonging is interconnected to the environment created around us and our own personal experiences we bring to these spaces.

Let's Really Talk About it:

The Picnic Table Method is a tool used to have honest and meaningful conversations about the outdoors. With The Picnic Table Model, I shared the barriers that youth and people typically face when trying to experience the outdoors. So what are we going to do about it? We know we need people of color in leadership positions who want to create change on the macro and micro level across all corners of the outdoor industry but why do we still deny the issues and allow complacency to sustain the status quo? Why do we allow this to continue and contribute to the exclusion of diverse demographics?

When people of privilege and power in the outdoors talk about wanting to diversify the outdoors, they often only extract the ideas of people of color and/or don’t bring them to the table where important conversations are happening. Both of these situations lead to the same outcome, no resolution.

If we truly want to have an outdoor environment for all, allies have to turn into accomplices, authority and influence need to be transferred to include a wider range of voices and perspectives, and communities of color need to be seen as valued stakeholders in the outdoors. People and organizations with resources need to invest in BIPOC leaders and organizations that are making meaningful changes in the outdoor landscape and their communities.

This multifaceted fight is one that is going to require “bail money and cornbread.” What I mean by this is that this fight to diversify the outdoors is going to be resource intensive, calling for a coordinated use of “good trouble” and a commitment to pushing boundaries in rooms where complacency exists.

This fight goes beyond acknowledging the need for change. It requires a radical and revolutionary approach. It requires us to actively contribute, participate, and take ownership in creating an accessible outdoor environment.

The well-being and inclusion of marginalized groups become integral to the flourishing of the entire outdoor community as a whole. When we, as the people who have been marginalized speak on how people of color are treated in the outdoors, it isn’t a mere suggestion to treat us better, it is a call for radical reconstruction. I need — we, the people currently in this fight need — the personal responsibility and proactive engagement from every person in the outdoor community.

I want to leave you with this question. If we truly want to make the outdoors a place for all, what are you willing to give up or do to see the outdoors as a space free of barriers for all to enjoy?