The (RE) Series: (Re)tracing My Roots

AHS NextGen Trail Leader, Thurman Hogan III, always had a love for the outdoors — something he thought made him an outlier in his family, until he re-traced his roots and found that this love for the outdoors was a shared passion, something passed down from generation to generation.

Thurman shares with us his story, his experiences, and his family’s connection to the outdoors and how it helped define his own.

Summer 2023 in the Colorado Rockies

Would you be willing to join me on a hike? In this four-part series, we will embark on a metaphorical hike through the outdoors.

Part one, '(Re)tracing My Roots,' serves as our starting point, like a gentle stroll in an open meadow, where I share my family's connection with nature and the outdoors. Part two, '(Re)defining The Discourse on the Outdoors,' is the steep ascent, where we confront challenging topics and biases in outdoor spaces. Part three, '(Re)imagining the Outdoors,' is where the elevation starts to taper, offering a vision of a more inclusive outdoor world. Finally, part four, '(Re)newing Our Hope in the Outdoors,' is the summit, where we look out on the horizon and bask in the accomplishment of hiking up uncomfortable terrain while discussing insights and solutions for fostering hope and change in our relationship with nature.

If you will, I would like to guide you on this journey.

My name is Thurman. I am an outdoor guide and activist, guru of all things operational in the outdoors, superfan of "The Office," and, in my own eyes, an outdoor celebrity with a fandom of two, my mother and grandmother. I'm in my 20s and have reached "uncle status" from those around me.

I love any activities dealing with the outdoors. Cooking on my Blackstone griddle for people, researching the newest and latest gear to drop, and taking Zoom meetings outside are a few ways I spend my days.

Simply put, the outdoors has, is, and always will be intertwined in my existence. I used to believe I was the outlier of my family, that I created this passion for the outdoors and nature myself. I was completely wrong. My love for nature and the outdoors was a love in existence before I was even born. It was passed down from my mother and her mother — it just looked different than I am used to today.

This story starts in a small Black Frontier town, Tatums, Oklahoma.

Granny's 78th birthday celebration

Granny's story starts in 1940. She attended the same school building her whole childhood with less than fifteen people in her graduating class. Her great-grandfather was a Native American chief, her father a white-passing Native American who worked for the railroad, and her mother a stay-at-home wife of seven kids on their acre homestead.

From an early age, nature and the outdoors were always a part of Granny's life. Their house had an outhouse and a tub on the front porch where they bathed. Every summer, from the end of school until the start of the next school year, Granny, her sibling, and her parents would head out to Western Oklahoma to pick cotton. The scars on her hands show how hard picking hundreds of pounds of cotton was, but it was vital to make money for their household. They would often plant watermelon seeds at the end of the cotton rows to harvest later as a relief for their hard work.

Their homestead also had plenty of livestock. One time, during a storm, their chicken coop blew away, and to keep the chickens from escaping, someone came up with the idea to bring the chickens inside the house. You can only imagine the sight of a feather-filled home on this particular day. Now, I'm no expert, but I am sure that didn't go over well. Rumor has it they were finding feathers for weeks and in random places.

Later in life, after marrying a baker, Granny relocated to Fort Worth, Texas. They bought a house and started a family. While raising a family of five, Granny took time to garden and tend to her yard. People often asked her for the "bulbs" of the Canna lilies she proudly grew to propagate and plant in their yards. She would have these big piles of weeds in the front yard that she hand-pulled to ensure her pristine St. Augustine grass was the talk of the block. What seemed like yard work was actually how she was in connection with the land.

As the years passed and her kids grew, they, too, had a connection with the land.

They would spend summers in Tatums. Just like their grandfather, they would walk everywhere. They, too, used the outhouse, bathed on the front porch, and curiously explored. Tatums was where our family up north in Detroit and down south in Texas would meet and form memories together. They would go to Wild Horse Creek to throw rocks and "hunt" with the BB gun their cousin had and sleep under the stars. Once the kids came back to the city, they were still active in the outdoors. They would play volleyball under the streetlights and just be kids. They continued to explore with a childlike wonder.

A connection to nature passed down from generation to generation.

As my mom and her siblings got older, they started their own families and moved around Fort Worth.

Now, comes me. My cousins and I all got passed down this connection to nature from doing as our parents did.

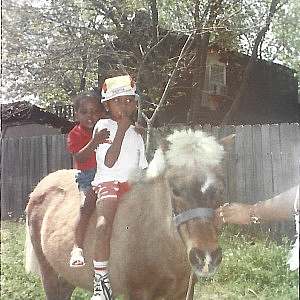

In many ways, Granny’s house was my generation’s Tatums. I shot my first squirrel with a BB gun Granny let me keep at her house. There, we would congregate as cousins, race in the street, dig mud pies, walk around, and try to find things to keep us entertained.

We had get-togethers, holiday dinners, and barbeques at Granny’s. One of my fondest memories is being ten years old sitting in the back of my grandfather’s ‘87 Suburban, sipping sun tea he made not saying a word but soaking up the environment around us. Being outside and in nature was something I always did as a kid but it wasn’t called being in nature.

Family camp out at Lake Whitney State Park in Texas

Granny’s connection to nature was based on dependency, survival, and enjoyment. What she experienced and seemed normal to her was passed down to her kids, and their kids, and will be continued with my kids.

I believe that it is important to walk through your own history to fully understand that this connection is in all of us.

For Black people especially, it is important to reflect and trace this connection to the land. It hasn’t been one without years of struggles. Yet, through decades of marginalization, this connection with the land and nature provided a community with those around us — experiencing the same circumstances and ultimately creating safety in numbers.

Before you and I can continue down this journey in the (RE) Series, I encourage looking into you and your family’s connection to land and nature, as this knowledge can serve as trail markers for the path going forward.