The (RE)Series: (Re)imagining The Outdoors

AHS NextGen Trail Leader, Thurman Hogan III, outlines a strategic approach for creating an inclusive outdoor space where everyone, especially youth and people of color, can feel they can fail with grace and be corrected with love.

In Part 2 of The (RE) series, I explored the historical disenfranchisement of Black individuals in outdoor spaces, introducing The Picnic Table Model to dissect barriers faced by youth and people of color. Geographical, financial, knowledge, and socio-emotional challenges were identified. I emphasized the importance of fellowship and representation for fostering a sense of belonging.

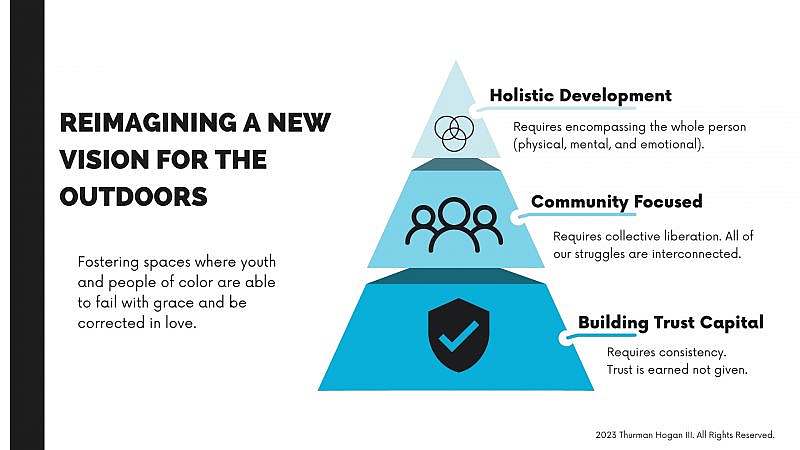

Part 3 introduces a “new” relationship-building approach rooted in BIPOC communities, illustrated through a graphic inspired by Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. The “new” approach emphasizes building trust while having a community-focused mindset, thus allowing holistic development. Lastly, it challenges traditional definitions of success in outdoor accessibility.

Reimagining the Outdoor Experiences

When we reimagine outdoor experiences for people of color in the outdoors, I want us to use a “new” approach that is deeply rooted in the practices of BIPOC leaders within their respective communities. These leaders have successfully used this approach on small and larger scales. It often serves as the unspoken answer to the question, ‘How are they able to be so strongly embedded in their communities?’ when people encounter the authenticity evident in their outdoor initiatives. With this approach, intentional and meaningful relationships are fostered. Relationships with people of color thrive on the foundational elements of trust, community, and holistic development. By embracing trust and a community-focused ethos, inclusivity is recognized and valued within these communities.

As someone who appreciates the power of visuals, I attempted to capture the essence of this approach through a graphic. Drawing inspiration from Abraham Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the graphic symbolizes the prioritization of fulfilling basic requirements as a prerequisite to achieving holistic development. In this way, our “new” approach embraces a spectrum of needs and experiences, ensuring that inclusion in the outdoors is not just a concept but a lived reality.

A note has to be made that in this approach, there will be growth by individuals. Under no circumstance are you to take credit for this growth and go into any community, especially those of color, with this approach and think you are saving them. Savorism has no place in any shape, fashion, or form in outdoor advocacy work and in general.

I intentionally didn’t name this approach as it is something that BIPOC communities have always done and belongs to the people. These three elements are the bedrock on which meaningful relationships are built, and humanity in marginalized communities is restored.

Building Trust Capital

A natural and necessary component of this approach is centered around trust, specifically building trust with you and people of color. Trust is the foundational piece in starting to build meaningful and intentional relationships. The rationale for trust being the foundational piece is that, without trust, it becomes challenging to encourage youth and people of color to engage in outdoor activities. This is especially true if they lack prior experience or have limited exposure to these environments.

When trying to build trust, know that you are not entitled to their trust; it is earned. Building trust comes with an understanding that you will be rejected and have to prove your intentions multiple times. You have to show you are invested in them. Consistency is required to build trust in any relationship. As a consequence, this means that we have to be constant with youth, their parents, and their families. We have to build trust with the ancillary communities they are a part of, such as the schools and the staff in those schools.

Practical Application of Building Trust

Every summer, the organization I work for, Black Outside Inc., takes 15-18 high school-aged youth backpacking in the Colorado Rockies through what we call The Ascent. This is a week-long experience that encompasses flying from San Antonio to Denver, driving to our base camp an hour away, acclimating for a period, backpacking with 25-pound packs up 2,000 ft of elevation change, making camp in Indian Peak Wilderness, descending, visiting local partners, and then catching a red-eye return flight back to San Antonio.

Initially, the commitment is a lot for first-time backpackers. Parents who have never really allowed their kids to go out of state for a week, especially in the mountains of Colorado, with people not in their family structure, should naturally have some reservations. As an organization, we recognize that this can be hard for some, so we have multiple information sessions, practice hikes with the youth, and answer any and every question they may have. The first questions typically are bear-related and deal with showers and pooping in the woods.

In the summer of 2023, there was a kid that we felt needed to go on The Ascent trip. We reached out multiple times, but we got a lukewarm response. There was interest by the youth, but the parents were the ones we had to convince. Our Executive Director had multiple conversations on the phone with the parents, answering all of the questions that the parents had. There was one phone call that lasted over an hour where it was just breaking down the trip and showing that we, as an organization, were serious about their youth coming. While the kid wasn’t able to come on the trip, a seed was planted for next year’s trip. Not every conversation or phone call leads to getting youth outside. Oftentimes, it’s more about building trust with families through personal invites and consistently reaffirming that we are here for them.

Community Focus

Now that we have laid the foundation of trust, we can start to become community-focused. Community -focus requires a basic understanding of collective liberation, which includes acknowledging that all of our struggles (personal, societal, etc.) are intertwined with each other and affect us all. Subscribing to collective liberation requires us to unlearn and abandon the individualistic ideologies that are ingrained in us. It requires us to address the “ism” that causes all forms of oppression and affects communities of color.

Collective liberation is a powerful and deep topic to discuss. It deserves its own space and series to unpack, but I encourage you to take a deep dive into what collective liberation means and includes. Know that it isn’t something that’s easy to put into practice. Collective liberation is a tool we can use to enact meaningful change and is more important than ever, especially today.

For the sake of this series, I want to focus on the interconnected struggle portion of collective liberation. As I have gained trust, I can know what struggles (internal and external) are affecting the people I want to build relationships with. I have to understand how these struggles affect the other members of my community. Often, if one is experiencing a struggle within a community, others are experiencing the same thing. These struggles create needs that exist in the community I serve alongside. To help guide them to the next phase of holistic development, I have to alleviate some of those needs.

Practical Application of Being Community-focused

There are two examples of how we put this into practice:

During the height of the pandemic, programming for us as an organization slowed down as everyone was affected by the stay-at-home orders. As an organization, we recognized that a host of factors were impacting our communities. Factors like: our youth doing online school, overall change in household income due to stay-at-home orders, and Black-owned business suffering due to lack of customers. We knew we had to do something. With the local Black-owned businesses, we bought meals for our families and delivered them. We drove to their houses, dropped off food, and caught up from a distance. We wanted to take the burden of cooking a meal off caregivers and just give them time to relax.

It was our first trip to Colorado (2020). We, as a staff, intentionally made space for an older youth, seeing how beneficial this trip could be for them. We had checked in with all our participants the night before to make sure they were ready for the early flight. The morning of, everyone showed up except for them. We reached out, and they told us that they weren’t going to come since they didn’t have a ride. We had about an hour before departing, and one of our program directors decided to call them an Uber to the airport. They arrived, and we all made the flight. It didn’t matter the cost as long as they were able to get there. Getting the youth to the airport was solved swiftly and without question, which most of the people on the trip didn’t know. It was second nature.

In both cases, there were needs (internal and external) that needed to be met. Sometimes, these needs can be small and easily solved by providing rides, and other times, they can be arduous and complex, like crafting a unique experience centered around things our youth face daily. Having a community-focused ethos is strong within our staff, and we are always actively trying to be better and evolve.

As a staff, through dynamic visioning, we can find ways to support the communities around our youth. This means providing a day for Black men to heal through yoga, a summit for mothers to decompress and feel supported, thinking of ways to include teen parents in our programming, and providing a safe space for trans and non-binary youth in the outdoors. All of their struggles are our struggles.

Holistic Development

By now, you see how building trust and being community-focused has helped create an environment where youth and people of color can focus on healing and developing to the fullest. Holistic development requires encompassing the whole person. When we are helping participants develop holistically in the outdoors, we can see them change physically from the rigor of outdoor activity, feel they can regulate emotions, know how to communicate how they feel, and be empathetic to others around them. We see the physical, emotional, and mental components grow in harmony.

Practicing holistic development sees the complete picture that youth and people of color are presenting. It recognizes the fragility some may face but also acknowledges the resilience they present day after day. For some kids, it’s recognizing that they come from rough or hard backgrounds yet still make it to school, are on the honor roll, and want to go to college.

Not every person of color has a story where they had to fight all their life to get where they are. This doesn’t discount them as they face their own set of challenges. Holistic development empowers youth and people of color, whatever their background, and helps them feel supported, nurtured, and valued.

Practical Application of Holistic Development

The best example of holistic development I can give you is our summer camp for Black girls.

Camp Founder Girls is America’s first historically Black summer camp for girls. With roots dating back to 1924, our organization resurged the camp in 2019. From the top down, Black women are in leadership roles and run the camp. I am just there to move heavy boxes, pick up small treats for the camp staff, and be the camp uncle who gives out freeze pops. Girls from all over the US fly into San Antonio for this week-long experience. For some girls, it’s their first time away at summer camp and, for some, a yearly opportunity. We have girls from all walks of life and social classes together.

At Camp Founder Girls, we are intentional about everything from the products given out to the sliding scale offered to those who need it. For some parents, it’s like dropping off your kid at a relative’s house for a week. During this week, we have four pillars that are unpacked and explored throughout camp: strength, bravery, creativity, and confidence. The girls make chants, build lifelong friendships, and are always supporting their peers. Every year, the night before leaving camp, we have a talent show. This show is filled with singing, dancing, and “Black girl magic.” Often, there is a little one who has stage fright, and the audience will start to sing the song to help them out. Typically, about halfway through the song, the little camper is singing the song with their whole heart and hitting all the high notes. At the end, a standing ovation is given in celebration of her. On day one, they were scared to be away from their parents, but by the last day, they were sad to leave their cabin and sisters.

By having a program that is intentionally planned, directed, and led by Black women, we can craft an environment where young Black girls can be their true selves. We create an environment free of judgment that pours into our Black girls so they are proud to be a “CFG Girl.” The parents understand what we are doing and can see their daughter come back confident and more comfortable with their Blackness. I know camp is only a week, and our continuity with the girls is short, but sometimes holistic development is about planting seeds that will flourish later.

Defining Success

With this approach, it is important to note that “traditional metrics” or Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) like the number of youth served per year should play a secondary role when determining success in ventures that serve marginalized communities. When creating access for youth and people of color in the outdoors, we should focus on the quality of the experiences and environment that we are creating.

There is a difference between creating access for 10 people in a way that nurtures them to develop holistically versus managing 100 people and their outdoor experiences. Numbers can often misinterpret the root causes of people’s needs and situations.

When working with marginalized communities, traditional KPIs and metrics do not capture the complexities of the socioeconomic hardships these communities face.

We need a nuanced and qualitative approach to assess the impact of the initiatives taken when working with youth and people of color. I know this approach to defining success goes against what we are taught when judging success. It is important to challenge our way of thinking, which doesn’t tend to promote equity. The challenge lies in acknowledging and understanding the wholeness of a story.

The Big Picture

The outdoors should be a space for the growth and self-discovery of youth and people of color. Achieving this vision requires actively building trust, serving the community, and supporting holistic development.

Implementing this “new” approach takes time, but by prioritizing people, we restore their humanity and create genuine connections.

Each step builds on the previous, making progress smoother. Building trust through sweat equity and consistency makes addressing community needs more manageable. By valuing and assisting individuals, we engage in shared experiences and recognize that we don’t have to solve all problems at once. This patient and strategic approach is crucial for creating an inclusive outdoor space where everyone, especially youth and people of color, can feel they can fail with grace and be corrected with love.